Charles Bellairs befriended Thomas Bradshaw-Isherwood whilst the pair were at university together at Oxford, in 1837, and the families became inextricably linked when Charles married Thomas's sister, Anna Maria Isherwood, in 1839, and Thomas married Charles's sister, Mary Ellen, the following year. During Charles's first visit to Marple Hall, in 1838, he kept a 'journal' describing in detail the events and conversations that took place, particularly between himself and Thomas's father, John, then Squire of Marple Hall. This article, written by M. A. Robson and published in Listener Magazine in 1954, describes a great deal of the content in Charles' own words and give a fascinating insight into the times and the people concerned.

Charles Bellairs befriended Thomas Bradshaw-Isherwood whilst the pair were at university together at Oxford, in 1837, and the families became inextricably linked when Charles married Thomas's sister, Anna Maria Isherwood, in 1839, and Thomas married Charles's sister, Mary Ellen, the following year. During Charles's first visit to Marple Hall, in 1838, he kept a 'journal' describing in detail the events and conversations that took place, particularly between himself and Thomas's father, John, then Squire of Marple Hall. This article, written by M. A. Robson and published in Listener Magazine in 1954, describes a great deal of the content in Charles' own words and give a fascinating insight into the times and the people concerned.

A Jane Austen Clergyman in Real Life

M. A. ROBSON on the journal of Charles Bellairs

From Listener Magazine 25 November 1954

(Also broadcast on BBC Radio's the Third Programme in 1954)

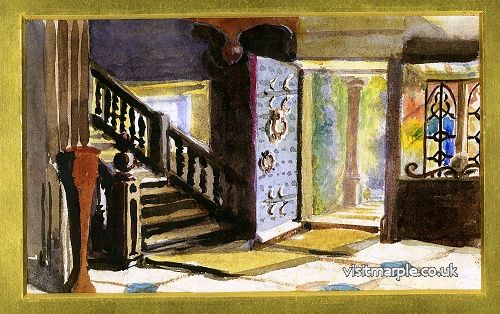

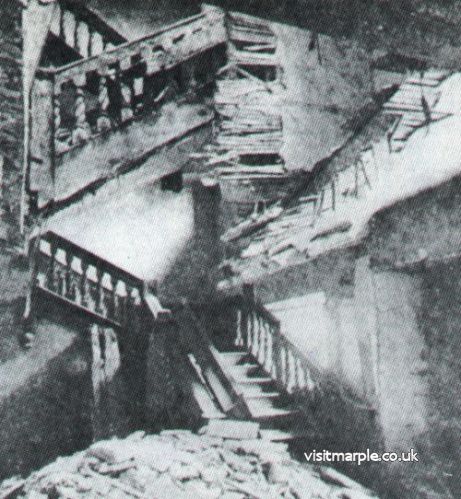

DURING the summer I was invited to the house of a country doctor in Yorkshire. On entering the dining room my first impression was of a profusion of books and walls covered with pictures. One picture in particular took my fancy: it was a small watercolour and a first glance revealed a splash of gold, brown, and orange. Studying it more closely, I realised that it was the entrance hall to some old house. My host, seeing my interest, told me it was the hall and staircase of an Elizabethan house in Cheshire. The painting had been done in 1910. The doctor then showed me a copy of a daily newspaper dated earlier this year: it contained a photograph of a staircase almost buried beneath plaster and masonry. The caption above it said: 'Marple Hall falling into disrepair'.

Above: The painting of the hallway of Marple Hall described in the article.

Below, right: The stairs as they were in the newspaper article.

Marple Hall has been the property of the Bradshaw-Isherwood family for generations. In the 400-odd years of its existence, many strange affairs have taken place within its walls. A few, a very few, are still remembered today. Legend has it that during the Civil War, Esther Bradshaw, daughter of the house, fell in love with a young Cavalier called Legh, who lived nearby at Lymme Hall. One night, after dining with the Bradshaws, Legh was deliberately misdirected to a treacherous mere-pool, for he bore despatches that authorised the destruction of the Roundhead-occupied Marple Hall. Esther, watching her lover depart from the house, saw him make his way towards the swamps, but she was too far way for her cries of warning to be heard, and Legh, with his horse and despatches, vanished beneath the mere-pool, from which the name 'Marple' was derived. Esther dies a year later, and her ghost is believed to walk the corridors still.

Marple Hall has been the property of the Bradshaw-Isherwood family for generations. In the 400-odd years of its existence, many strange affairs have taken place within its walls. A few, a very few, are still remembered today. Legend has it that during the Civil War, Esther Bradshaw, daughter of the house, fell in love with a young Cavalier called Legh, who lived nearby at Lymme Hall. One night, after dining with the Bradshaws, Legh was deliberately misdirected to a treacherous mere-pool, for he bore despatches that authorised the destruction of the Roundhead-occupied Marple Hall. Esther, watching her lover depart from the house, saw him make his way towards the swamps, but she was too far way for her cries of warning to be heard, and Legh, with his horse and despatches, vanished beneath the mere-pool, from which the name 'Marple' was derived. Esther dies a year later, and her ghost is believed to walk the corridors still.

Evidence of a less gruesome nature gives a delightful picture of the hall in its palmy days, just over 100 years ago. This picture is provided by the 'Journal of Charles Bellairs'. This gentleman, seemingly a mixture of Boswell and Beau Brummell, was the great grand father of my host, Dr. Alderson, and in 1838 he had paid a visit to Marple Hall and written down his various impressions in a continuous narrative form, which has never been published. For want of a better name, I have called his narrative a 'Journal'.

With no preliminary canter, the journal gives us a pretty good idea of the sort of man young Bellairs was: 'In the year 1837' he writes, 'I became an undergraduate of Oxford, and being the younger son of a country clergyman, rector of Bedworth, I went there on a small allowance, but I was determined not to demean myself by making inferior acquaintances . . . I soon became friendly with the best men of the College, and amongst them was a young lad, only just eighteen, the only son of a country gentleman in Cheshire, whose income I afterwards understood was about £5,000 a year, and who resided in a very curious old mansion where his ancestors had flourished for many hundreds of years in much the same social position as they enjoyed at this moment. I was soon told by another man of the same college that the family was considered peculiar but that the old squire was mighty respected and that he was a great favourite with his tenants and dependants. He mixed but little with the neighbouring gentry'

This undergraduate was an Isherwood; and Bellairs lost no time in becoming friendly with him. Soon he received an invitation to spend a few days at Marple in the summer of 1838. He was to be met at the Royal Hotel in Manchester, and taken to Marple by carriage.

The Main Gates to Marple Hall on Stockport Road.

'According to this arrangement', writes Bellairs, 'I went from Liverpool to Manchester by rail, and at the hotel I found the carriage waiting for me. I shall never forget this equipage, as it drove to the hotel door. It was a high, spare, antique chariot of the colour of mustard, made only for two inside, no seat behind, but a high box in front for the coachman . . . On the box sat one of the biggest coachmen I ever saw, in white livery with blue facings, and at the carriage a very spare thin lad of a grinning footman with long tags and spikes at his shoulders. There were a pair of fine large, black, well-fed horses, and the landlord paid great deference as he bowed me to the door. We had a drive of about eleven miles, which was accomplished in an hour and a half. We entered a shabby-looking park ... by a handsome pair of wooden gates with stone pillars, and at the end of about a quarter of a mile drove into an ample courtyard facing the front of the house ... I saw at once that it was an ample Elizabethan mansion without any modern additions, and that it was the sort of home you might expect for an old-fashioned county gentleman with his four or five thousand pound a year. The footman got down from his lofty perch and made a great rat-tat at an old oak door studded with iron nails ... The door was opened by a stately middle-aged butler in black who seemed as if the place had been made for him and he for the place. He informed me that his master would be pleased to see me in the oak parlour'.

Non-stop Talker

If there is a 'hero' in this journal, then it is old Squire Isherwood. He is a non-stop talker, and Bellairs seems to have recorded his speeches verbatim. Here is his opening address:

'"I am glad to see you, Sir! You are a friend of my only son; I am sorry he is not well enough at present to come downstairs to receive you, but he will see you in his own room. He is my only son, Sir, and it is of great importance that he should live till he is of age, for the property is strictly entailed, and if he should unfortunately die before he is one and twenty, it will go to the Salwin family and not to my daughters. I have however directed my lawyers to get everything ready against his coming of age, and the very moment the clock strikes twelve, Sir, this disagreeable entail will be cut off, so I hope he will get better. I have the principal physician to see him every other day from Manchester, whose fee is six guineas. You are at Oxford, Sir; I am of Trinity College, Cambridge, where I took my degree, and then I prepared myself for writing my three Dissertations under the advice of my famous friend Mister Le Bas. I shall have much pleasure in presenting you with an autograph copy; and I am told by my learned neighbour Mister Cresswell that the Preface is unanswerable; but you judge for yourself.

'"And now, if you will allow me, I will introduce you to my three eldest daughters, who usually occupy the room adjoining this. Two of them I think you have already seen. The eldest, Anna Maria, is fond of riding spirited horses. The second is named Miriam. She is a good accountant, and I much wish she had been a boy. The third is named Magdalene . . . she plays on the harp and sings with tolerable taste. Besides these three you will find with them their great friend and companion Miss Davenport, the daughter of my neighbour Sir Salisbury Davenport, who has invited you to dinner tomorrow evening when you will see his fine old place. The rental of his estate, Sir is about the same as mine, but (I would not like his daughter to hear it) I believe his estate is mortgaged, which materially diminishes his income, and as he lives at much greater expense than I do, I am afraid he is at times inconvenienced".

After being introduced to these four young ladies in their own little parlour, which was rather shabbily furnished, the old Squire offered to show me my room, as it was nearly time to dress for dinner; and on shutting the door, he remarked for the first time, that his wife was not at home: She is gone to the sea-side, Sir, with her maid. She frequently goes for two or three months together, but I have so many home occupations, I do not much miss her". On crossing the hall again he showed me the library door: "That", he said, "is the room in which we usually assemble for dinner. We do not occupy the drawing room unless we have a considerable number of guests. It is true the Vicar and his wife dine here today, but we do not consider them company"'.

Gloomy but Comfortable

Bellairs is now conducted up to his room. The first staircase he mentions is the one that formed the subject of the watercolour and the newspaper photograph I mentioned earlier. Bellairs writes: 'On ascending the principal staircase I observed on the first landing amid several pictures, a full-length figure in chain-armour fitted on to a wooden block, with a plaster face of most forbidding aspect. On the second landing was an enormous jar filled with pot-pourri, and on the third landing was a picture of a melancholy lady weeping over her husband's grave ... Turning to the right, I was shown into my room ... The furniture was all of oak, and though everything was gloomy, the fire made it comfortable ... As there were four young ladies in the house, and I was the only young gentleman, I probably took some pains with my toilette. On descending the stairs, I made my way into the library, where were seated the four damsels, all dressed in plain but becoming white dresses, with bouquets of flowers, the old Squire, and the Vicar and his wife who had just arrived. Dinner was soon announced, and we all walked in state to the other end of the hall and entered the dining room'.

Bellairs is now conducted up to his room. The first staircase he mentions is the one that formed the subject of the watercolour and the newspaper photograph I mentioned earlier. Bellairs writes: 'On ascending the principal staircase I observed on the first landing amid several pictures, a full-length figure in chain-armour fitted on to a wooden block, with a plaster face of most forbidding aspect. On the second landing was an enormous jar filled with pot-pourri, and on the third landing was a picture of a melancholy lady weeping over her husband's grave ... Turning to the right, I was shown into my room ... The furniture was all of oak, and though everything was gloomy, the fire made it comfortable ... As there were four young ladies in the house, and I was the only young gentleman, I probably took some pains with my toilette. On descending the stairs, I made my way into the library, where were seated the four damsels, all dressed in plain but becoming white dresses, with bouquets of flowers, the old Squire, and the Vicar and his wife who had just arrived. Dinner was soon announced, and we all walked in state to the other end of the hall and entered the dining room'.

After a detailed description of the dining room, Bellairs gives us an amusing impression of county table manners: 'The old gentleman was extremely polite and courteous to everybody, except his own daughters, whom he snubbed on every occasion, and he invariably called them "the girls". If they monopolised the conversation more than he liked, he peremptorily said: "Girls, hold your tongues!" if one of them was about to commence on a new tart or a cake, he said to the butler: "Tell the girls to leave that tart alone, till some is wanted". The old butler entered freely into the conversation if it turned on any of the tenants or parishioners about whom he thought he knew better than his master. During dinner the Squire alluded frequently to his Cambridge career, to Mister Le Bas and the three Dissertations against Infidelity, and woe be to any of the three girls if they opened their mouths till he had finished his say.

Marple Hall Dining Room in 1902.

'When the ladies had withdrawn, the Squire said to me that he hoped I found his carriage easy; and when I had thanked him very much for his great kindness in sending it so far, and remarking how handsome his horses were, he replied that he was thinking of having a new carriage; but he was putting it off till next year, as he had just had to pay for an expensive monument to two daughters in the church, and it was not quite convenient for both to be paid for in the same year; but his girls wished for a carriage called a Britschka and which he intended to order.

'"These girls", he said, "call the carriage in which you came by the name of 'Wasp', partly on account of its colour and partly because it is spare and narrow. There is another, much larger carriage in the coach-house, to which they have given the name of 'Bumble-bee', partly because it is broad and rather of a yellowish-brownish hue, and partly because at a distance its sound resembles the humming sound made by those insects. I do not myself approve of nicknames, but there is also a third carriage, an open one, which they call ' Spider', on account of the extraordinary height of the hind wheels. But altogether Sir, they are respectable and comfortable, and tomorrow you will probably have an opportunity of seeing them, and also my horses"'.

Tour of the House

In the morning, the Squire proposes to take Bellairs round the various rooms in the house. '"There are not many of them", he said, " and they are by no means spacious, but the incomparable topographist Doctor Ormerod has been pleased to say that he considers this house to be one of the most interesting in the county"'.

In his garrulous, informative way, the Squire leads Bellairs round, describing each room with terrifying accuracy. About one room in particular he waxes eloquent: '"This small apartment", said the old man, "is vulgarly called by my wife 'King Charles' Closet'. I do not at all approve of it myself, but I have to put up with many things that I disapprove of, of far greater importance than this. I have not told you before, Sir, that my wife is of a very romantic turn, and it frequently leads her to excess, as in the fitting-up of this closet. That extraordinary and indeed ludicrous figure on its knees in the centre is intended for the martyred King Charles I, and he is supposed to be kneeling before that table perusing his Death Warrant. You are, perhaps, not aware that Judge Bradshaw, who presided at his trial, was born in this house, and that I am descended from his eldest brother. I am not proud of the connection, Sir, though I believe he left considerable wealth to the family, but my wife considered that it ought to be illustrated by that ridiculous figure before you. She selected several pieces of old armour from the collection in the hall, and had a kneeling-block made on which they were fitted. The hair, which flows over the shoulders from beneath the helmet, was cut off her own head, when she had a fever. The purple velvet boy-breeches were made from the skirt of a worn-out dress, and the leather jack-boots were made by a neighbouring shoemaker; and as the figure is kneeling, you can see at once that the soles have never been used. I do not like to remove it, Sir, as it would probably produce discord in the house, but I assure you, Sir, I am ashamed of it"'.

'He then took me', says Bellairs, 'up the circular staircase into the drawing-room ... In a deep recess there was an organ on which, he informed me, his wife played Handel, Haydn, and Mozart. "It usually", he quaintly added, "fell to the lot of an unbeneficed and unmarried clergyman to have to blow the bellows". The room was handsomely upholstered in gold and crimson of much more modern style than any I had seen before. Taking me to a bay window, he showed me a beautiful view of hill, wood, and water; and pointing to a tall factory chimney about a mile distant, with a large modern mansion close to it: "That", he said, "is the great drawback to the landscape before you. The piece of land on which that factory is built formed part of this estate, but my eldest brother, who then owned it, and who was too fond of horses and dogs and who had entire control of the estate, was obliged to sell nearly 1,000 acres to discharge his debts, and amongst them that piece which is now in view of these windows. If I had married Lady Davenport, as I believe I might have done, there would have been twice 1,000 acres added to this estate ...You will see Lady Davenport this evening, Sir, —a charming person— but I grieve to think they must be living beyond their income, and I greatly fear, as I said before, that we shall before long see the result of it"'.

'He then took me', says Bellairs, 'up the circular staircase into the drawing-room ... In a deep recess there was an organ on which, he informed me, his wife played Handel, Haydn, and Mozart. "It usually", he quaintly added, "fell to the lot of an unbeneficed and unmarried clergyman to have to blow the bellows". The room was handsomely upholstered in gold and crimson of much more modern style than any I had seen before. Taking me to a bay window, he showed me a beautiful view of hill, wood, and water; and pointing to a tall factory chimney about a mile distant, with a large modern mansion close to it: "That", he said, "is the great drawback to the landscape before you. The piece of land on which that factory is built formed part of this estate, but my eldest brother, who then owned it, and who was too fond of horses and dogs and who had entire control of the estate, was obliged to sell nearly 1,000 acres to discharge his debts, and amongst them that piece which is now in view of these windows. If I had married Lady Davenport, as I believe I might have done, there would have been twice 1,000 acres added to this estate ...You will see Lady Davenport this evening, Sir, —a charming person— but I grieve to think they must be living beyond their income, and I greatly fear, as I said before, that we shall before long see the result of it"'.

Visit to the Davenports

After further descriptions of various rooms in the Hall, and covert references to the vice of gambling, Bellairs mentions his visit to the Davenports' house: 'In the evening we drove off in Sir Salisbury's carriage for the dinner party at his grand old place ... It is one of the finest specimens in England of a Tudor house, and has the handsomest drawing-room in Cheshire. There was a party of twenty-four to dinner: all the military from the neighbouring town, the Rector and his wife, the curate and his wife, the lawyer and his wife, and the remainder was made up of the neighbouring gentry. We dined in the great entrance-hall, and after dinner it was proposed, as there were several officers (one of whom I was told was a Sir Michael Somebody, who had at that time two bullets in his inside) that there should be an impromptu dance in the room adjoining the Hall, and whilst we were in the middle of it, the old Squire and Bumble-bee were announced on their way back from the Manchester Agricultural Dinner, and we were told the horses were not to be kept in the cold. [Later] I over-heard the old gentleman tell Lady Davenport that he was pleased with his son's college friend, and that when I had passed my "little-go" he intended to invite me again, for he said it was agreeable to find in the present day a young man who was respectful and not over-talkative, and who knew how to behave to his elders! I found the oscillating motion of Bumble-bee rather trying after the dinner and the dancing, but we arrived home in safety'.

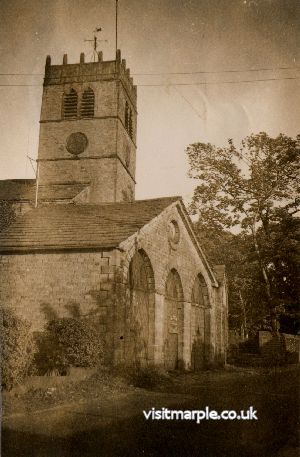

At the end of the week comes a description of a country Sunday, 'which was observed with great respect', comments Bellairs, 'but not with becoming strictness. The church was a mile and a half from the house, and there was a large coach-house and stabling abutting into the churchyard, for the accommodation of the Hall, with a large stone coat-of-arms over the entrance. Immediately after breakfast Bumble-bee appeared at the door, and behind it a servant with two ponies for the girls. The old Squire entered the coach, and as he drove though the village it was a signal for the four public houses to close their doors. One landlord would say: "Here comes Old Squire Shut-up!"

At the end of the week comes a description of a country Sunday, 'which was observed with great respect', comments Bellairs, 'but not with becoming strictness. The church was a mile and a half from the house, and there was a large coach-house and stabling abutting into the churchyard, for the accommodation of the Hall, with a large stone coat-of-arms over the entrance. Immediately after breakfast Bumble-bee appeared at the door, and behind it a servant with two ponies for the girls. The old Squire entered the coach, and as he drove though the village it was a signal for the four public houses to close their doors. One landlord would say: "Here comes Old Squire Shut-up!"

'The Hall pew was, in fact, the north end of the chancel, curtailing the altar of half its legitimate dimensions. You ascended two or three steps into it, and underneath was the family vault. The door had a large coat-of-arms on it, and the floor was carpeted. The pew contained an easy chair and a table, cushioned seats, and a fireplace, fender, and fire irons. On the panel was a brass plate informing the public that this pew and the vault beneath were private property. 'There were curtains round that portion which was not protected by walls, and altogether the Squire and his family had a very cosy time of it. Two or three dogs accompanied us, and at the end of the prayers the footman entered and made up the fire. The old Squire made loud responses and paid marked attention to the sermon; and when the prayers were over, he rose and looked over the door, drawing the curtain aside to note who was at church and who was absent.

'Before leaving, he pointed to the monument, the payment for which had deprived his girls of a new carriage for the present year. "That weeping lady", he said, "in marble, is placed in order to satisfy the romantic disposition of my wife, whom it's supposed to represent. She is weeping over the ashes of her daughters, which by a stretch of fancy are supposed to be enclosed within that marble urn. You will observe that she is plucking a half-blown moss rose from the wreath; and a butterfly, the emblem of immortality, is flying away towards Heaven. My daughter", he added, "was engaged to be married to my learned neighbour Mister Cresswell, who assisted me so much with my Dissertations. All his love-letters were buried along with her, some that are no doubt extremely interesting, and also an engagement ring he had given her. I did not approve of the engagement, but I never expected she would live to marry him, on which account I was more reconciled to it, Sir. It amused her in her delicate state of health, and it also gave me the advantage of many intellectual conversations with him. At her death, Sir, he wrote two volumes on the burial service and presented each member of the family with a very handsome bound copy. And to show, as I believe Sir, his great respect to us, proposed to two more of them, but it was not desirable, and he found an excellent wife elsewhere: my two daughters making up for his disappointment on that occasion by undertaking the office of bridesmaids"'.

The interior of All Saints' Church with Marble Plaques.

At the conclusion of the sermon the Squire usually went into the vestry, and if he had approved of the sermon, invited the Vicar to dinner. After a hasty luncheon, round came Bumble-bee again for the afternoon service, as nothing but the direst necessity prevented the family from going twice to church.

'The remainder of my visit, which extended towards the close the [following] week, was spent in walking, driving, and paying visits and receiving the Davenports at dinner; and I felt on leaving that, on the whole, I had made a good impression'.

The journal ends abruptly, and with two surprise statements, but Bellairs seems to have had no idea of the odd impression left by his final paragraph: 'My next visit in the following Spring was to attend the dear old man's funeral. I believe almost his last words were the mention of my name to his eldest daughter, who became my wife by the end of the year'.

This, then, is the substance of the journal of Charles, later Canon Bellairs, and Rector of Bolton Abbey. With his snobbery, his conceit and his preoccupation with other people's money, he remains an urban proof that men like Jane Austen's Mr. Collins really did live, love, woo and wed a hundred years ago.

Finally, here's an interesting letter written by another of Charles's descendents to M. A. Robson in response to his radio broadcast of the Journal:

16.XI.54

Dear Mr. Robson,

Your broadcast talk was very interesting, especially to me, a grandson of the Rev. Charles Bellairs.

I did not know of the existence of the journal, presumably it is in the possession of Dr. Alderson and if this gentleman would be good enough to lend it to me to read, I should be very much obliged.

At the end of your talk, you likened the Rev. Bellairs to "Mr. Collins", but (I) do not understand on what grounds you based your opinion. There was nothing in the quoted extracts from his journal to lead to any such conclusion.

Perhaps you are unaware that the Bellairs family of Royal descent is one of the oldest in the Kingdom and Charles was at least the social equal to the Isherwoods, even if his branch of the family at that time was not so wealthy.

Yours truly,

John Bradshaw Isherwood Bellairs.

Background to this article

In October 2003 I received an e-mail from a lady who owns a bible containing hand written details from the family trees of the Bellairs and Bradshaw-Isherwood families. Around the same time I discovered a photocopy of the article above from a 1954 issue of Listener magazine in a scrap book at Marple Library. In December 2003 I reproduced the Listener article on the web site with an appeal for descendants of Charles Bellairs to get in touch and soon after made contact with Marmaduke Alderson, former mayor of Bristol, and Charles's great great grandson. The Bradshaws and Isherwoods were both ancestors and cousins to Marmaduke's family. He knew Richard Isherwood well (Richard was godfather to his brother) and visited him whenever he had the opportunity.

In October 2003 I received an e-mail from a lady who owns a bible containing hand written details from the family trees of the Bellairs and Bradshaw-Isherwood families. Around the same time I discovered a photocopy of the article above from a 1954 issue of Listener magazine in a scrap book at Marple Library. In December 2003 I reproduced the Listener article on the web site with an appeal for descendants of Charles Bellairs to get in touch and soon after made contact with Marmaduke Alderson, former mayor of Bristol, and Charles's great great grandson. The Bradshaws and Isherwoods were both ancestors and cousins to Marmaduke's family. He knew Richard Isherwood well (Richard was godfather to his brother) and visited him whenever he had the opportunity.

In 2009 Marmaduke published the full Journal of Charles Bellairs, which his father had transcribed from Richard Isherwood's copy in 1941. He has kindly provided me with a copy of this fascinating document and I can recommend it most highly to anyone who has an interest in the history of Marple Hall.

To obtain a copy please send £5 to cover publishing and postage costs to:

Marmaduke Alderson, "Gannow", 312 Canford Lane, Coombe Dingle, Bristol, BS9 3PL.

Marmaduke has also provided a number of family photographs taken at Marple Hall.

These are now featured in The Virtual Tour of Marple.