VIII. A Changing World 1911-1939

1.World War I

The first signs of a changing world came in 1911 in a great national railway strike which began in the North West of England; this not only showed that railwaymen were tired of long hours and low pay, but were now sufficiently organised to demand better conditions on a national level - and get them. This was followed in 1912 by a coal strike, which had a very serious effect on the railways.

Outside the station horsedrawn cabs and carriages might still wait to meet passengers, but the early years of the 2Oth C, saw the start of privately owned petrol driven omnibuses. At first in Marple, as elsewhere, they connected with trains and ran from Marple Station to Mellor, Compstall, and Hawk Green. But soon the operators realised that where the railway service was poor, infrequent or indirect, they could draw passengers from the railway - and so the 1900's saw the start of a bus service between Marple and Stockport, where the bus could provide a service much more convenient and not much slower. As yet buses were unreliable and uncomfortable, but it was an augury for the future.

The first motor bus in Marple on 21 October 1908. Edith Elizabeth Bridge (nee Clayton) sitting and Mr Clayton - bus owner - standing. From Marple Local History Society Archives.

The storm clouds burst in August 1914, when World War I broke out, and immediately the Railways were taken under Government control. As the war progressed, the Railways increasingly felt the pinch; more and more of the staff left for the ranks, voluntarily at first, then under conscription, so that the Midland for instance lost nearly 30% of its total staff to the armed forces, and of these one-third were killed. Railway Works became munitions factories, and locos, wagons and carriages were sent all over Europe for military traffic. Despite losses of men, equipment and repair facilities, the railways were called upon to handle an unprecedented amount of military traffic, for which they got little reward. In this situation, something had to give: maintenance and repairs to track, stations, engines and rolling stock fell into arrears, so that by 1918 one-fifth of all the engines in Great Britain were awaiting repair. The strain soon began to take its toll, and by the end of 1916 the Midland had withdrawn some of its best Manchester-St. Pancras trains, and most of the more exotic through coaches. In January 1917 further savage cuts were ordered by the Government, leaving the Midland with a basic service of local and semi4ast long distance trains, while fares rose 50%. Overcrowding was severe. and timings slow, but the railways had little alternative. The G.C. suffered equally badly, but its services to Marple, Hayfield and Macclesfield were local and non-competitive, so that even by 1918 the service was only a couple of trains down on 1914. However the N.S. service over the Middlewood Curve ceased at the outbreak of war. But by 1918 Midland services at Marple were just under half what they had been in 1914; almost all the lavish pre-war through coaches had disappeared; the only Main line train to call was in fact an overnight through coach from Manchester Victoria to St. Pancras - in fact this was the only service linking Marple and Victoria. For the rest Marple was served by locals between Central or Stockport and Chinley, Sheffield, Buxton or Derby. In such a crisis there was no place for through workings to Liverpool, Blackburn or Bristol, or holiday trains to Blackpool, Southport, Yarmouth or Lowestoft. Instead troop and munition trains ran day and night.

2. The Aftermath of War and the Grouping (1918-30)

The war ended in 1918, but the Railways remained in Government control until 1921. Some lines, such as the L.N.W. and Midland, were in relatively good shape, and some of the Midland's pre-war through coaches and trains calling at Marple were restored such as those to Victoria; but others such as the Blackburn services were never restored. Other lines however were in very poor shape, having been worked to death and starved of essential maintenance; it was obvious they could not survive unless supported by stronger companies such as the Midland. War-time control had also removed the worst of pre-war competition which had led to a proliferation of duplicating and triplicating services and routes, and shown the advantages of some form of unified working. It was therefore felt desirable to amalgamate the 150 or more railway companies into regional groups. This process was known as the "Grouping" It was originally intended to form separate Midland and L.N.W. based groups; but eventually the Midland joined its old rival, along with smaller companies such as the L. & Y. and N.S. to form the London Midland and Scottish Railway Company (L.M.S.). Despite the large number of lines owned in the North West, the G.C. was obviously part of the Eastern group, which also included its old ally the G.N.; this was the London and North Eastern Railway Company (L.N.E.R.). Coming into existence on 1st January, 1923, these new companies took some time to knit together, particularly the L.M.S., where the rivalries of Midland and L.N.W., such antagonists in the past, and differing in practice on nearly every point, did not really die down for over a decade. The old G.C. and Midland Joint Line was now L.M.S. and L.N.E.R. Joint, as was the former G.C, and N.S. Macclesfield line; the C. L.C. was also joint between these two great companies. The L.M.S. adopted Midland Red for its locomotive and carriage livery, which infuriated L.N.W. men; the L.N.E.R. however adopted a pleasing shade of apple green for its engines. and continued the old G.C. (and G.N.) coaching livery of varnished teak. While the elaborate lining-out and armorial embellishments of the Company days soon disappeared, the liveries were thus very similar to what had gone before. With this and the gradual re-instatement of many of the old Midland through services, which continued into L.M.S. days, it might seem at Marple that only the names of the Companies had changed, and railwaymen both high and low looked forward to a return of the palmy pre-war days.

But those days had gone for good, though it took railwaymen a long time to realise it. The Railways never received proper compensation for war damage; a return to financial stability was sought in an all round increase in rates in 1919, with passenger fares rising to 75% above pre-war level, goods rates being doubled, except for coal, and small merchandise rates up 150%. This however was a very unfortunate move, as it made the Railways look even more expensive compared with the growing number of private hauliers taking to the roads. Before the war there had been about 82,000 petrol driven goods vehicles, mostly employed in connection with the railways; by 1922 alone there were twice as many, and as often as not competing with the railway. In a railway strike of 1919, traffic was lost in bulk to the private hauliers, and the increase in rates referred to above merely made the matter worse. What is more the Railways by law had a "Common Carrier" obligation; that is they had to quote public and fixed rates for all goods carried, and they were obliged to accept anything. The road hauliers, by contrast, could pick and choose what they liked, and could easily undercut by charging slightly less than the Railways' published rates. The road hauliers paid little tax, and nothing for the maintenance of the roads they used. As if this was not enough, in 1920 the Government flooded the market with 20,000 army surplus motor vehicles at knock down prices; many ex-servicemen snapped these bargains up, and set up as road hauliers. Two such ex soldiers from Cheshire bought a Ford "Tin-Lizzy" van on their service gratuity. One day when carrying a load from Liverpool, they came racing down Brabyns Brow; they lost control, and crashed into a horse drawn lorry going down the hill, knocking the lorry into the sunken front yards of the houses at the foot of the Brow, killing both Driver and his horses. The driver was "Old Yarwood", who delivered the parcels and sundries from Marple Station for the Railways, and he was just going home for his dinner. This tragedy, still recalled by older residents, of runaway road vehicle crushing the slow, and somewhat old fashioned, railway carrier is strangely symbolic of the changes taking place in the years following the First World War. Goods traffic at all the stations in the district began to decline, except coal, which continued to increase as more and more houses were built. What is more Marple was becoming a preponderantly residential district for Manchester and Stockport, a process began by the Railways in the 1860's, and less of a manufacturing community. The cotton spinning mills and other textile works began to decline, especially in the depression of the 30's, under the pressure of foreign competition. Further troubles, notably the General Strike of 1926, did little to help the Railways out of their plight.

The Motor Bus Terminal, near the Jolly Sailor on Stockport Road.

Meanwhile the Railways were losing passengers as well to the roads; in Marple the bus operators soon captured much of the Stockport traffic, as Marple Station could hardly be called conveniently situated, and the trains infrequent, while Rose Hill had no direct services to Stockport, and Tiviot Dale Station was not convenient for much of the town. Some attempt was made to combat competition by introducing more trains worked by a "Sentinel" Steam Railcar of C. L.C. origin; this looked like a conventional coach from the outside, though a miniature steam locomotive was concealed in the bodywork at 6ne end. This had some success, but many were won to the bus, which could often set you down almost on your doorstep. Buses never drew much Manchester traffic from the Railway, as the train service was good, and the road indirect; but the growth in private car ownership in the immediate post-war years was phenomenal, and many took the roads for all journeys. Marple was however growing all the time as new houses were built in Mellor, Ludworth, Hawk Green etc., and so the numbers of passengers using the stations, particularly Rose Hill, actually increased, though there were fewer main line passengers at Marple.

It was not really until about 1930 that the Railways woke up to the grim reality of road competition, having been used to nearly a century's monopoly; nor did the Government, and it was not until the 30's that Road Traffic Acts were passed to license and regulate road passenger and goods transport. By then it was too late, and the railways were in a slow general decline, though there were many specific improvements. In such an economic climate, with accompanying rising wages and the reduced working day, it was impossible to keep up appearances as the Midland or G.C, had done, and by the mid 30's L.M.S. engines in particular had become generally shabby and dirty, except on express trains, under the rigid economy drive of Lord Stamp, President of the L.M.S. It is probably as well that from the 30's all but express passenger engines on the L.M.S. were painted black! Nor were things any better on the L.N.E.R. services.

But as yet Marple station still had a large staff, though the lampmen and shunters were cut out as an economy measure in World War One. Stations in the district were still well maintained - even too well maintained, if this story is anything to go by. One year, in the late 20's, the boarding was being removed from the interior of the long footbridge over the goods loop linking up platform and Brabyns Brow, in order to paint it. The Station Master, Mr. Walsh, took umbrage at this, saying there was no need to take the boarding out, and that he would stop this nonsense, and write letters of complaint to both companies. This he did, and accordingly a Works Inspector arrived one afternoon on the 1.30 p.m. train from London Road. He asked the paint foreman what all this 'to-do' was, and was told that they were only taking down the boarding to paint it. The Inspector was a sensible fellow and replied "Oh well, we can't stop that then, can we? Now what time do the pubs shut?" On being informed that the "Midland" was open by special license until 4.30 that afternoon (it being market day) there he went, and stayed until closing time!

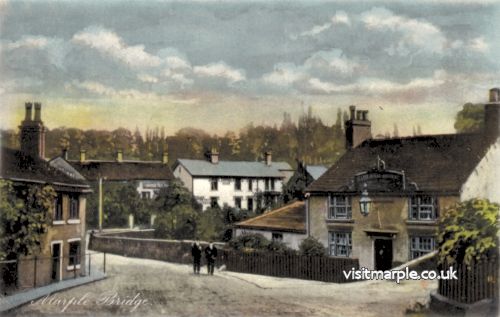

A hand-coloured postcard showing the Midland at Marple Bridge.

3. Train Services between the Wars

With the grouping, the point of much of the pre-war competition and duplication of services became irrelevant, as the two great rivals, Midland and L.N.W. were now in the same camp. One benefit was the renaming of many stations with similar names belonging to different companies to avoid confusion. In our district on the Macclesfield line for instance, "Poynton" station actually about 1Y2 miles from the place, better served by the ex L.N.W. station, was renamed "Higher Poynton". But it is surprising how long some of the competitive services lasted, and of course L.M.S. and L.N.E.R. continued to compete. Midland services to Liverpool gradually faded away, and those that remained were for the benefit of cross country passengers from intermediate stations rather than London; but the L.M.S. if anything promoted the Midland Manchester route, though this was via the "new line" and not Marple, while Blackburn, East Lancashire and Manchester Victoria were considered the province of Euston. In the changing economic conditions of the 20's there was no room for much of the lavish pre-war provision of through coaches, especially as many of them had lost their point, that is competition.

By March 1927, four years after the grouping, the war time total of 18 Midland line services at Marple had risen to 32, which was however less than the 1910 total of 38. Of these the majority were stopping trains between Manchester Central and Derby, Sheffield or Buxton. There were also one or two peculiar workings such as an Altrincham-Marple working, and a Chinley-Liverpool semi-fast train which called at Marple. A couple of day time trains ran to and from Manchester Victoria, calling at Marple, of which 1 each way was a St. Pancras through coach. For some reason the Up overnight Manchester Central-St. Pancras continued to call at Marple, to take up the Manchester Victoria coach. There was also a through train from Victoria to Nottingham which called each afternoon at Marple, and ran fast to Ambergate, but then turned into a semi-local service calling at such unlikely places in Nottinghamshire as Langley Mill and Ilkeston Junction. Gone however were the regular exotic through workings to Bristol, or Lowestoft, and an increasing number of trains calling at Marple had Chinley as their terminus, where connections were made with all manner of services. But the L.M.S. provided a somewhat better local service than before and at last there was a reasonable business service to and from Central, arriving at 9 a.m. and leaving at 5.8 p.m. in the evening, though the journey took over 50 minutes. The L.N.E.R. local service continued. to flourish and grow, so that by July 1938 the timetable shows 31 trains to and 32 from London Road; of these about half used Marple as a terminus which would have kept the loop and bay well occupied. The total of 63 L.N.E.R. trains was over 25% higher than the G.C. service of 1910; with the 32 L.M.S. trains the 1938 total of all trains, up and down, both Companies, was slightly higher than the pre-war figure of 87, though well below the staggering 1898 total of 109. If the 1938 service lacked the main line aura of pre-war days, it was more frequent and convenient; there were more peak hour trains, though there were still long mid-morning and afternoon gaps; if you were unfortunate to miss the 2.23 p.m. from London Road, it was a long wait until 4.10 p.m. for the next train home to Marple.

By 1938 the main line service still lingered on, but was increasingly patchy; there were two services to, but none from St. Pancras - one was a daytime Manchester Victoria through coach and the other was the overnight train from Central and Victoria which marshalled up at Marple. The late afternoon Manchester-Nottingham semi-fast train continued to call at Marple, but now ran from Central, with a connection from Victoria (also calling at Marple) at Chinley. As before, however, the bulk of the service was made up by locals between Manchester and Chinley, Sheffield, Buxton or Derby. The L.M.S. ran quite a few shuttle services between Marple and Stockport Tiviot Dale only, rising to 6 or 7 each way on Saturdays, giving quite a reasonable service combined with the Central service of 14 each way on weekdays and 17 on Saturdays. But due to the disadvantages already mentioned, the 'buses seized the lion's share of the business, though the shuttle was busy on Saturdays. The July 1938 timetable shows some interesting summer trains calling at Marple. One, recalling the most exotic pre-war trains, was a Saturdays Only train from Yarmouth Beach to Manchester Victoria via South Lynn, Melton Mowbray, Nottingham and Marple, while in the other direction a Blackpool to Sheffield Saturdays Only train called as well. Every day of the week a fast holiday train ran from Nottingham and Derby to South port Chapel Street via Marple and the C. L.C.

The engines and coaches of the 1920's differed little from before the war. The L.N.E.R. continued to use 6 wheel coaches of great antiquity, which were extremely rough to ride in; some regulars said they had triangular wheels while others maintained they were square, but it was generally agreed they could not possibly be circular. Nobody had a good word for L.N.E.R. coaches, and in a council minute of 1926 we read that the Mellor Parish Council had approached Marple Council enquiring whether they were "favourable to the formation of a joint committee of representatives of the Marple, Ludworth, Compstall and Mellor Councils with a view to approaching the L.N.E.R. for improved conditions as regards cleanliness and lighting of railway coaches running between Marple and Manchester". Whether they ever formed such a joint committee is not known, but there was certainly no improvement for some years yet. L.N.E.R. trains were generally composed of 8 coaches, all compartment non-corridor stock, with one first and five third class carriages, and two brake thirds (half guard's van, half compartments). The morning and evening peak trains were strengthened to 11 coaches by the addition of one more first and two third class coaches. Most coaches were steam heated and gas lit, though a few of the newer ones had a primitive form of electric light, while as yet lavatories were rare.

The 3:05pm Manchester (London Road) to Macclesfield Central train pulled by Class A5 4-6-2.T. No 69823 near Rose Hill on 8 September 1956.

L.M.S. trains were rather better, largely because of the coaches inherited from the Midland, which had had a head start ever since the abolition of the second class in the 1870's. By the 20's, almost all L.M.S. trains serving Marple were composed of 8 wheeled compartment coaches, with upholstery much superior to those of the L.N.E.R. On suburban trains to Central 9-coach sets were used, with 3 first class coaches -a very high proportion. The Derby slow trains were often composed of 4-coach sets, with a Brake third, composite first and third coach, third class coach and brake third, giving the equivalent of one complete coach for parcels, and only three for passengers; on busy trains two four coach sets were amalgamated, giving four separate vans, a rather excessive provision! In the 1930's the L.M.S. was replacing these old 8 wheelers by modern steel panelled, electrically lit corridor or compartment bogie carriages, just as the L.N.E.R. was introducing 8 wheelers, These were made up into sets consisting of only 5 coaches, as they were longer than the 6 wheelers they replaced; as the coaches often came from other lines no 2 within a set were ever the same!

A feature of Marple station at this time was the large number of children from Marple Bridge, Ludworth and Mellor (then all in Derbyshire) travelling daily to New Mills Grammar school, outward at about 9 a.m., returning by the 4.18 p.m. train; the Headmaster used to complain that his school hours were fixed by the railway timetable. Consequently station platforms were crowded with school children, and, as you can imagine, they were not always as well behaved as they might be. An ex-scholar recalls one day at New Mills when some second formers were trying to take by storm a compartment held by first formers, who tried to keep the door shut by holding on to the window strap. Unfortunately their forces were equally matched, and in the strain something had to give - and it was the window, which shattered. Next morning the Station Master stopped everybody on the platform at New Mills until the culprits owned up. Another ex-scholar recalls that an old Midland Dining Car used to run on the 4.18 from New Mills, and they used to play shov'ha'penny on the tables, and that the goals were "permanently and indelibly marked" thereon! In 1936 however Mellor became part of Cheshire and the scholars Went to Hyde Grammar School instead, and presumably the outrages between New Mills and Marple ceased. For some years a railcar ran between Hyde and Marple for the school children's benefit.

On the locomotive side, L.N.E.R. trains were generally hauled by 2-4-2 tank engines of M.S.L. vintage, but later on these were ousted by more powerful engines such as 44-2 G.C. tanks. L.M.S. locals continued to be hauled largely by superannuated Midland express engines, at least into the mid-30's, and such things as the 4-2-2 Johnson "Spinners", often over 40 years old, were often still seen on easy turns like the Manchester Victoria through coaches. But following the introduction of the "Class 5" 4-6-0 mixed traffic engines ("Black Fives") and the Jubilees (both designed by Sir William Stanier the L.M.S. Chief Mechanical Engineer) on the main line between Derby and Manchester in the years just before the war, the 440 Midland "Compounds", which since 1909 had worked the best trains out of Central, began to appear regularly at Marple on L.M.S. local and semi-fast trains. Goods still remained in the hands of pre-grouping 0-60's, some of them dating from the 1870's and 80's, though by the late 30's more powerful 0-80's and 4-6-0's were also seen on through goods trains.

On the whole, the physical appearance of the railway changed little in this period, except that as old Midland type lower quadrant signals became due for renewal, they were replaced by more up to date upper quadrants (that is signals which show "proceed" when raised instead of lowered) on tubular steel posts of standard L.M.S. design, though some ex Midland signals lasted into the late 1960's. In the drive for economy, Oakwood and Marple Goyt Viaduct Signal boxes were closed in 1930. These boxes had only served to shorten the sections between Romiley and Marple Wharf Junction, and Marple and Strines respectively. With the development of "Track-circuits" in the early 2OthC., it was now possible for a signalman to know the position of a train he could not see, perhaps many miles away. This opened the way for the use of "Intermediate Block Signals", set in mid section to divide it into two, and with the track circuit indicating exactly where a train was. Accordingly in the Marple area, Intermediate Block Home Signals were provided where Oakwood and Marple Goyt Viaduct Signal boxes had been, permitting a reduction in staff, but without any loss in line capacity. One piece of work done at this time was the renewal of parts of Marple Viaduct. The spaces in the spandrels of the stone arches had originally been filled with clay, but over a period of years in the 30's this was dug out and replaced with concrete, which was more stable, but with less "give" in it than clay.

4. The Macclesfield Line

There was a considerable growth of housing, particularly the ubiquitous "semi", in Marple, Mellor, Ludworth and Hawk Green, resulting in a 20% increase in the number of L.N.E.R. locals at Marple comparing 1938 with 1918 or 1910; there was less growth around Strines, due to the remote site of the station and the lack of suitable building land. But at Rose Hill the growth was positively phenomenal. In 1920 only a handful of houses were visible from Rose Hill station, and only perhaps 30 were within a quarter of a mile; but by 1938 the station was engulfed in a sea of red brick. Semis, and high class detached houses spread the entire length of Stockport Road to the top of Dan Bank, and down all the side roads, such as Cross Lane, Dale Road and Bowden Lane former fields were developed to form new estates such as Claremont Avenue. In the ten years around 1930 the aspect of the Rose Hill area had completely changed from rural to suburban. The growth was no doubt stimulated by the existence of the station, and in turn the new housing stimulated a great increase in the number of trains. In 1910 there had been 9 weekday services each way on the line; by 1938 there were 11 trains to and 13 from Macclesfield, and 5 services each way, introduced in 1935 or thereabouts, which terminated at Rose Hill, in recognition of its new importance as a suburban station. All told then, there were 16 Up and 18 Down services at Rose Hill by 1938, nearly double what it had been twenty years before. These "turn back" services ran round at Rose Hill and the loco usually ran tender first to Manchester. Most trains ran to or from London Road, but one train started from Guide Bridge and another from Ashburys. To cater for residential traffic, trains left Macclesfield at 7.20 a.m., and Rose Hill at 7.44 a.m., running non-stop from Hyde to reach London Road at 8.14 a.m., followed by the 6.13 a.m., from Macclesfield (depart Rose Hill at 8.38) which was non-stop from Romiley, reaching Manchester at 8.56 - 18 minutes from Rose Hill. In the homeward direction the 5.6 and 5.33 p.m., were first stop Romiley, reaching Rose Hill in 22 and 19 minutes respectively: the L.N.E.R. was obviously making a conscious attempt to stimulate residential traffic.

Railway workers and passengers posing at Rose Hill Station.

The Macclesfield to Bollington shuttle was also intensified, to combat bus competition, and by 1921 had reached 15 journeys each way, though this was down to 12 by 1938. There were in addition odd Saturdays Only shuttle workings to and from Higher Poynton and even Middlewood High Level. The shuttle was for some time after the war worked by an experimental Westinghouse petrol-electric railcar introduced by the G.C. in 1912 on the basis of the success of similar railcars in Hungary. It had cost £2,500, ran at a maximum speed of 40 m.p.h., and had seats for 50 passengers on tramcar-style reversible seats, with hanging straps, hopefully for standing passengers. It was not really a success, and was sent to end its days on the Bollington shuttle, where it earned the name of the "Bollington Bug" because of its buzzing noise. It was third class only, and was regularly seen at Rose Hill, as it provided the Saturdays Only late night service each way between Romiley and Macclesfield. It was eventually withdrawn in 1934, and replaced by a steam railcar. The Macclesfield-Buxton summer service via the Middlewood Curve was restored in 1922, and ran erratically until 1927, when passenger services ceased to use the curve for good. There was some housing development at High Lane, and to a small extent around Middlewood in the 1920's and 30's, but not anywhere near the stations, which retained a quite rural aspect. Middlewood in particular remained a peculiar back water - as it still is; an old railwayman who was the Porter-Clerk at the High Level station there for many years from 1933 onward, recalls that the early morning workmans' train to Manchester had only two regulars - and one of those lived in the Station House. There were some regulars, cotton workers in the mills of Bollington, who changed at Middlewood to and from New Mills Newtown, and on Tuesdays and Thursdays the Muffin Man used to come from the bakery at Bollington and take his wares to stations down the Buxton line. Middlewood was also apparently a favourite place for pigeons to be released, due no doubt to the great tranquillity of the surroundings!

Surprisingly, however, between the Wars, Middlewood was a hive of activity on summer Saturdays, with day-trippers from Manchester, Gorton, Hyde, Ashton etc. There is a pleasant hollow near Middlewood station, and here a Mr. Cooper erected two large Tea Rooms; "Cooper's Hollow" was particularly popular with Sunday School parties, with plenty of space for games. Special excursions were run on summer Saturdays, which having disgorged trippers at Middlewood, ran to Macclesfield to stand to return later in the evening to pick up the excursionists. The Porter recalls taking over 300 tickets on some Saturdays, and seeing the platform jam-packed with returning excursionists. It is difficult today to imagine Middlewood as a Mecca for excursionists.

It was however also apparently a Mecca for burglars, who found its isolated location ideal for their activities, but in fact never got any money, as the 30/- (£1.50p) float was kept well hidden in the bottom of the ticket stamping machine. After one break-in the detectives came and found the footprints of a rather distinctive size 8 workman's shoe on the chair, which was therefore wrapped up, and taken away to trace the owner of the footprint. All sorts of people were questioned - campers in "Cooper's Hollow", passengers at the station and so on - but none had shoes to match the footprint. The mystery of the footprint was however solved when the other porter clerk at the station, who was a short man, arrived for duty, and asked what all the fuss was about. When told about the footprint, he replied "oh they're mine - I stood on the chair to turn t'light out!" The culprit of the crime was however never found.

As on the Marple services the locomotives provided by Gorton shed were ex G.C. Robinson 4-4-2 tanks, or occasionally older M.S.L. machines. The coaches were the same as on the Marple and Hayfield services, though the Rose Hill "turn backs" were formed up of half of the old 8 coach sets of 6 wheelers; one half set was thus without first class accommodation, so some ancient first and third lavatory composites were dug up and attached to the half set lacking first class.

But despite these improvements, on both Marple and Rose Hill lines, the railways were losing ground to the roads on a national as well as local scale; the buses and now the private car were creaming off many passengers, while those left expected higher standards of comfort than before. Wages and costs rose, business dropped off in the wake of a world wide depression, while the invisibly subsidised road continued to despoil the railways who were still labouring under legislation designed to protect the public and traders from a railway monopoly which no longer existed.

Ex-G.C. C13, 44-2 Tank Engine No.67425 brings a Manchester-Macclesfield Local round the sharp curve from Marple Wharf Junction in 1956. (E. Oldham)